How We Can Be Wrong About Our Parents.

If you know my father, you know what a kind man he is. You know that he has spent his life teaching and serving others. You also know that he is genuine enough and humble enough to tell you about his mistakes. I have often heard him say, “if all else fails, you can always use yourself as a bad example.” So here’s to you, Dad. A story about the two of us in our less flattering moments, a story in which I am not nearly so innocent as I thought. This is my bad example story.

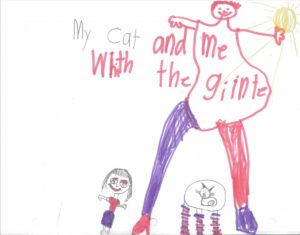

There is a piece of crumpled paper I have carried in my heart for years. It’s scribbled full with stick figure drawings and tiny illegible handwriting. This scrap from the past nags persistently at my attention, insisting upon the scrutiny of my adult mind. Because, forgotten in the corner of my heart, these childhood and teenage perceptions have the power to distort my stories, the all-important ones I have been telling myself about my own life.

Among the scribbles on that crumpled paper is a drawing of my father. I am holding his hand. Our mouths are straight lines. I can tell you that this childhood image of my father is all wrong, and the story I write about it here is going to be wrong too. I am not kidding when I say this. I have rewritten this story dozens of times thinking that a newer version will be better. But each version is either excessively long, embarrassingly personal, yawningly philosophical, suspiciously one-sided, pathetically skeletal or… well… just wrong. Perhaps this project was doomed from the start. My readers may be critical, bewildered, or downright bored. I have given up on the preambles, qualifications, limitations, and fine print. It is going to be all wrong and I am going to write it anyway. I am going to close my eyes and walk straight off the proverbial cliff.

Here it is: When I was a child, sometimes I was scared of my father.

I realize I have just broken a taboo for conversations among good company and polite people who love their parents. A whole cohort of my readers are going to stop right here. My lovely mother-in-law, who reminds me to be very careful what I say, is cringing. Of course, nobody has perfect parents, but that is entirely beside the point. I plunge recklessly forward.

What I remember most about my father is that he was tall. Over six feet in height, he towered like a tree, strong and unbending with roots firmly gripping the solid ground beneath him. He was a giant and I was just a small human child and, sometimes, I was afraid of him.

Today, this seems unimaginable. My father is all gentleness and compassion. When I am sad or discouraged, I want my Daddy. And then I am all young again, and he knows all the answers. My Daddy hugs me and tells me to hang in there because things are going to be okay. I believe every word of it, when he says it. And I feel my root-shaped feet gripping the ground once again. Then he smiles and says, “Remember, it’s always darkest just before it turns completely black!” This makes me laugh. He always tells me this when I am sad, and it always makes me laugh.

But the father of my childhood seemed different to me. Maybe, I was just extra sensitive. Ask any of my ten siblings who was most likely to cry and they will all point at me. I would shrink into a quivering puddle of tears if my father ever said “damn it” and I perceived that he might be looking in my general direction. If he raised his voice, I cowered. If he scolded the lot of us, I was the one who took it personally.

To be fair, I should note that my father often took issue with the word “anger” and called it “exasperation” instead, leaning on a dictionary as if the meanings of words were fixed and immutable truths. But to me, as a kid, I could see no difference between these words. He could call it “exasperation” if he wanted to, but in my mind, he was just mad.

My father has always been a remarkably confident and self-assured person. Maybe, sometimes, his confidence got the best of him and interfered with his more introspective qualities. When he was really upset, perhaps that unshakable self-assurance encouraged his feelings of justification.

There was one episode that has become legend among the older siblings who remember that far back. I am the second oldest and was thirteen at the time. My father was upset about something. None of us remember exactly what it was, but the last straw was the fact that no one would confess to the crime. The possible culprits, five of us, were brought into his bedroom where he told us to kneel around the bed. That’s when he took off his belt and announced that he would spank every one of us with the belt, going around the circle as many times as necessary until someone confessed. We erupted in protest. We asserted our innocence. We complained, disputed, pleaded, and otherwise insisted that his plan was thoroughly unfair. He spanked us all.

Do you think this is horrible? I did. But I also thought it was horrible when I had to do the dishes, alone! You may ask: what kind of parent would spank their kids with a belt? Umm… pretty much every good parent in that generation. Every kid I knew was spanked by their parents. Back then, spanking was just good parenting 101.

This memory sticks with me, not because we were spanked with the belt, but because the circumstance struck us all as utterly absurd. Yes, Dad used to get mad, raise his voice and swat us on the behind. But we felt he was fair. This was the exception. What made my father so upset that he would rather punish four children unfairly than be remiss in punishing the single guilty party? I probably cried, for the same reason I always cried when my father was angry. He didn’t really hurt my bottom so much as he hurt my feelings. I could not believe my father would be so mean, and I was innocent! At least, that is the way I remember it: I was always innocent.

After the first round of spankings my father stopped. No one had confessed. His sure-rooted confidence faltered and his unshakeable tree swayed. Maybe my father was ashamed, because he didn’t make a second round with the belt as promised; he just put it away. Perhaps he realized it then, if there was, in fact, a guilty person in that room, it was probably not one of the five kneeling around the bed.

As far as any of us can remember, that was the last time my father ever used his belt for anything other than holding up his pants. Years later, when we were grown up and married, we were talking about this episode at a family party. My father overheard us and insisted we were wrong, that he would never do such a thing. He could not remember that episode that had burned permanent pathways in our brains along with a stinging redness onto our back sides. Ultimately, my confident, self-assured father had to concede that the story must be true. There were so many witnesses against him. And he sat there, a tree hunched forward, shaking his head in half disbelief. I remember marveling at this. He really didn’t remember. It was not part of his sense of self. This story, standing on its own, yielded an image of my father that was entirely foreign to him and the effect was disorienting, as if we had just introduced my father to a total stranger wearing his face.

I confess that I spent part of my adult life feeling a little hurt by childhood or teenage perceptions of injustice or favoritism. But now I just can’t sort it out. Was my father too angry or was I too whiny, the kind of kid that would make any parent nuts? And what about me? I yell at my kids often enough and have been known to swat their butts from time to time. I am pretty sure they think I am scary sometimes.

They say pride takes a chunk out everyone’s soul, before you learn how to be honest with yourself. And these are the hardest lessons, the ones where you discover your own weaknesses, blind spots or even self-deceptions. There I am, living my life, oblivious to my own failings, making more mistakes than I can count and all the while imagining myself to be a pretty good person. And then you realize that you have missed something critical and looking back it seems obvious. You should have noticed, but you didn’t. Thank God, life offers us a few scraps, a few brief moments of redemption.

Several years ago, I was chatting in the kitchen with my then seventeen-year-old son, Jake. “Someday” I said, “when you are older, you will make a list of all the things we have done wrong as parents.” He looked at me a little stunned. “What?” he said. “A list, Jake, you’ll make a list of all our mistakes.” Then he laughed and said “Mom, I have already started it.” I looked up, caught his eye and hesitated, and then I laughed, too. Not because I thought it was a joke, but because I knew it was true and I should not have been the least bit surprised. “Of course you have already started it. I should have known.” And I think I was smiling from ear to ear, when I said this. I felt proud of this son at this moment. The affection between us was palpable in the air, and I could have hugged him or kissed him. And I am sure he would have let me. But I had a skillet full of hamburger to fry and he had a dish rag in his hand, and there were things to be done. And it was enough anyway; it was already a heart-full of contentment seeing him stand there on the edge of manhood and knowing he could see my flaws.

And why do I cherish this moment so much? Why do I call it to mind so often? Why do I tell my friends about it? Should I feel proud of all my past and present blunders, the ones my son has so carefully chronicled for future reference? No, pride is definitely not the right word here. But I feel content, a certain quiet assurance. I feel this even though we all know that his list of my parental blunders will grow and grow. Because that is what we do as parents, in spite our best efforts. We blunder!

Perhaps screwing up is just part of our job description as parents. We overreact, underreact, punish unjustly, reward unfairly, miss the boat, come unglued, freak out, go berserk, hurt their feelings and then their pride. We lecture when we should bite our tongues and remain silent when we should have spoken. We are over-attentive one day and neglectful the next. We micromanage all the wrong things and drop the ball on others. We fail to notice, fail to listen, fail to be there when our kids were counting on us most. And our child scans the audience again and again looking for his Mom and Dad in a veritable sea of parents, but the poor kid will keep looking in vain, because this time we forgot to show up.

And in spite of all this, I have a sense that everything is going to be okay in the end. Maybe it was the smile on Jake’s face that told me this, that smile he had when he said he had already started the list. There was no bitterness in it, no resentment. It was a gentle smile, as cheeky and cheerful as the ones he gave me at age four, when his whole world was innocence, when Santa Claus was real and when it was still possible to believe that his was the best mom in the whole wide world. Yes, I think it was the smile that made me feel so happy, because he is old enough to know, old enough to see all my blunders and he had chosen to judge them gently.

But have I done the same for my own parents? The answer is: not always. Perhaps my father was a little too self-assured and, perhaps, I have always been way too sensitive. If I am honest with myself, I am not even certain I was entirely innocent. In the case of my father in his younger years, I suspect exasperation is a much better word than anger after all, even if a child cannot really perceive the difference?

Trying to puzzle this out 40 years later makes me realize that much of the hurt I felt as a child or young adult might have been based on entirely immature assumptions, childhood perceptions that once they took hold colored my world view from that point onward, seeping into the gaps left by the fragmented memories of youth. But I am wasting my time with this story. As an effort to sort out the rights and wrongs of the past, does any of this matter at all? I bet I am wrong about most of it anyway. All the “truths” in the stories we tell ourselves are composed of layers upon layers of misperceptions.

This is the one part of this story I feel absolutely sure about, that every perception is unavoidably a misperception. We cannot see into another’s soul. And, it seems, we cannot escape the injustice of our own perceptions. Walking down memory lane, we cannot help but judge our parents through the oversimplified lens of the child we were then, a child who was inexperienced, lacking pertinent information, and bewildered by the fact that the world is not fair. We imagine somehow that our childhood perceptions were entirely accurate, even though we know to be skeptical about the stories our kids tell us. Like the time my eight-year-old adopted daughter insisted that the clothes she was wearing were a gift from her birth mom. “No, Honey, don’t you remember, we picked those out together.” I guess that is the nature of memory, notoriously unreliable, all the gaps filled in by our honest but inaccurate perceptions of the world.

Even as adults we run into trouble with our perceptions. We judge the previous generation based on the values and standards of our own generation, a culture as different from the past as it is invisible to those of us who inhabit it. Then, possessing the advantage of hindsight and an insider’s view of our unique needs, we criticize the “obviously” wrong choices our parents made. We imagine we know exactly what the perfect parents would do and be. We hold up this uniquely customized parental ideal and compare it, point for point, against the parents we actually have and inevitably we are disappointed. We are quick to criticize parents who have the wrongheaded expectation that their kids should be just like them. But we don’t realize that we do the same thing to our parents, expecting them to be just like us. We forget that their personality, talents, and background are fundamentally different from our own, and, like all parents, they were blundering blindfolded through parenthood.

Children are not transparent like glass with their needs and desires self-evident to the beholder. Children are something entirely opaque, mysterious, and evolving. They are beloved creatures that bewilder and amaze us. Now that some of my kids have reached adulthood, I find this is more true than ever. They are entirely different from me and entirely their own. And this is as it should be.

A few years ago I was visiting my father. I don’t remember what we were talking about. I have no clue how the topic came up. But my father wrapped me in his arms and with tears in his eyes told me he was sorry for the hurts I felt as a child. “I don’t know why, Cindy, but I think I was harder on you than some of the other kids, and you didn’t deserve it.” I was surprised and touched by this confession from my self-assured father. And what strikes me is that even he doesn’t understand it. You can’t understand such things. You just do the best you can and who the hell knows what interferes with our deepest intention to be the best parents that ever lived? Who knows why we can’t get it right? Maybe we just can’t. What really matters is whether or not we can let go of that highly-polished image of what we think should be, so that we can fully embrace the tattered beauty of what is.

My father always loved me. That is something I have known even in the moments when I thought he was being mean or unfair. And if I just throw that one crumpled perception aside, the figures with straight lines for mouths, then I have a clear view of all the other childhood drawings in my collection. Daddy comforting me. Daddy making me laugh. Daddy reading to me. Daddy playing card games with me. Daddy defending me. Daddy giving me wise advice. Daddy always there for me. Daddy crying because he is so proud of me.

My father always loved me. That is something I have known even in the moments when I thought he was being mean or unfair. And if I just throw that one crumpled perception aside, the figures with straight lines for mouths, then I have a clear view of all the other childhood drawings in my collection. Daddy comforting me. Daddy making me laugh. Daddy reading to me. Daddy playing card games with me. Daddy defending me. Daddy giving me wise advice. Daddy always there for me. Daddy crying because he is so proud of me.

The truth is: my father’s love has been as unshakeable as his confidence. I have spent my whole life leaning against his sure-rooted tree of confidence that weathers the storms so well. I have sheltered under his branches and have been soothed by the cool gentleness of his shade. And I am thankful, that he was not all too plagued by self-doubt. If his strength is also his weakness, then he is just like the rest of us. I embrace all of it. I embrace you, Daddy. You have nothing to apologize for to me. I am the one that owes you an apology, for clutching so doggedly to a child’s oversimplified view of the universe. You were and are a great dad. The BEST! I cannot live without you. I have leaned on you so much and so long that my own tree would tip over if you were gone.

Dear Reader,

I embraced and abandoned this story like a clumsy kid with a yoyo. My father encouraged me even though this story was, admittedly, not his greatest moment. My mother, a therapist, pestered me about it, saying she needed it for one of her clients. It has been weeks since then. It’s still not right. It will always be wrong. Like my best attempts at parenting, it will miss the mark. I am just hoping that, somehow it is going to be okay anyway.

P.S.

Tonight I read this aloud to my 13-year-old son, Nick. He loved it. He told me how awesome it was. And then he said, “Mom, “I will never make a list like that!”

“You mean a list of my parental blunders?” I ask.

“Yeah, like Jake’s list. I will never do it.”

Yes you will, Nick.”

“No, I won’t. I promise. I will remember this day and I will never make a list.”

“Well, you might not make a list on paper, but you will in your mind.”

“No, Mom, I won’t!” His protests were so sweetly earnest.

“Honey,” I said, “You will make a list. And, trust me. It’s okay. That is how it should be. You need to do this. It’s part of growing up. How else will you know how you want to create your own life with your own wife and your own kids?”

He surrendered. “Okay, Mom, I love you.”

“I love you too!”

At the very bottom of this page you will find a place to post your comments. I love hearing from you. If you find something useful here, share my post with others. Also, on the right you will find a place to subscribe to my blog. Subscribers receive an email as soon as a new post appears.

Absolutely beautiful. 🙂

I remember your dad well. He would make me laugh, and is one of three men (wait! Make that four–my son is very good) who can make puns till I cry. And yet, he would have intimidated me, too, had he been my dad. I think you have captured what most of us feel both as adult children towards our parents, and as parents towards our children. Isn’t that what growing up is all about? Learning to forgive our parents, ourselves, and our children as we progress towards becoming like God? Thank you for writing these blogs. They make me very happy!

I am just grateful he is my dad. And I am grateful to understand him better. It’s hard being a parent when the stress and responsibilities are high. Like tonight, when I was packing the suitcases for the move to DC tomorrow morning, and I am so tired and overwhelmed and not exactlly the model of patient parenting, yelling at the little ones to get back in bed. My dad must have been in that spot often. How often I must have taken it personally. I will need to reassure my girls in the morning that I was tired and cranky and it’s not their fault.